Banking on Reliability: Inside a Major Australian Bank's SRE Transformation

Some thoughts after observing a two-year reliability transformation that's still ongoing

I've been fortunate enough to observe up close at one of Australia's big four banks. It's been nearly two years now and they're still at it, but there are some genuinely useful patterns here that we should probably be applying to our own client work.

The thing that struck me most wasn't the technical implementation - that was fairly predictable Prometheus/Grafana stuff. It was how they approached the people and culture side that made all the difference.

They Started by Hiring Their Way Out of the Problem

Most organisations try to train their existing people into SRE roles, which usually takes forever and often doesn't stick. These folks did something much bolder - they hired a proper cohort of principal and chief engineers directly from Google. Not just one person to lead the charge, but an actual team of people who'd lived and breathed SRE at scale.

It was expensive, obviously, but it solved two problems immediately. First, they had instant credibility when trying to convince traditional banking teams to change how they thought about reliability. When someone who helped build SRE at Google tells you how to run incident response, people listen. Second, it created this gravitational pull - other engineers actually wanted to learn from these people rather than being forced through training programmes.

For our client work, I think we're being too conservative about recommending this approach. Yes, it's a significant upfront investment, but we've seen too many transformations stall because the internal team didn't have the confidence or experience to push through resistance. When you're trying to change decades of "that's not how we do things here," having genuine expertise makes all the difference.

Incident Management Became Their Cultural Trojan Horse

Here's something clever that we should definitely steal: they used incident management as their primary vehicle for cultural change. Instead of starting with dashboards or SLOs, they focused entirely on getting blameless post-mortems right first.

The unexpected outcome was what they called the Weekly Incident Review Forum. It started as a basic process requirement but accidentally became the most effective learning mechanism in the entire organisation. Hundreds of people showing up voluntarily every week - including the EGM and CTO - to learn from each other's failures.

What made it work was the visibility. Reliability work that used to happen in silos suddenly became this shared learning experience. Cross-team patterns started emerging. Leadership could signal priorities just by showing up consistently. And most importantly, it built the psychological safety that everything else depended on.

But here's the crucial bit that gave it real teeth: accountability became very public. When teams committed to fixing issues or implementing improvements during these forums, everyone was watching. If the same problems kept appearing week after week, or if committed timelines weren't met, it wasn't just the individual engineer who felt the heat - it escalated up the chain quickly. We're talking about senior managers and even directors having uncomfortable conversations when their teams repeatedly failed to deliver on public commitments.

The beauty was that it wasn't punitive for individuals - the blameless post-mortem culture protected people from finger-pointing. But it created organisational accountability that was impossible to ignore. When you've got hundreds of people, including the CTO, watching whether your team actually follows through on what they said they'd do, it changes behaviour fast.

I think we should be positioning incident management much earlier in our QCE approach. Not as something you do after you've got proper observability, but as the foundation that makes everything else possible. It's something teams can start immediately, regardless of their current tooling situation. And we should be more explicit about designing in this accountability mechanism from the start.

They Measured Things People Actually Care About

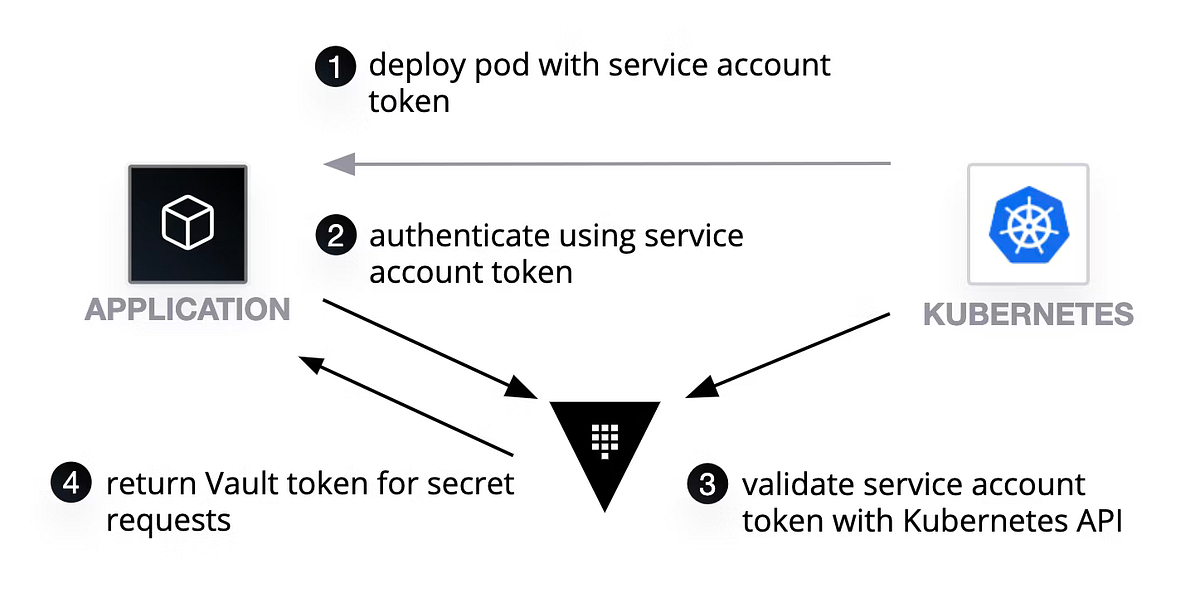

The technical platform was fairly standard, but their approach to SLOs was genuinely clever. Instead of the usual CPU and memory metrics, they focused on business functions that non-technical people could understand:

- Can developers push code to GitHub?

- Can employees log into Microsoft 365?

- Can customers complete a banking transaction from start to finish?

This immediately made reliability discussions relevant to executives. No one outside engineering cares about microservice response times, but everyone cares about whether the business can actually function.

The really smart bit was how they handled legacy systems. You can't instrument a mainframe from the 1980s, so they didn't try. Instead, they built black-box probes that constantly tested critical business functions from the outside. They measured the outcome - was the transaction successful? - rather than trying to understand the internal state of systems that predate most of the team.

This let them set SLOs for even their most opaque systems, which is something we should be suggesting more often. We get too caught up in trying to instrument everything perfectly when sometimes testing the end result is more practical and valuable.

The Ownership Shift Was Messier Than Expected

They reconfigured alerting to go directly to service owners instead of through the traditional multi-level support queues. Classic "you build it, you run it" philosophy. Predictably, this created significant pushback from development teams who weren't used to getting paged at 3am.

Their approach was pragmatic rather than confrontational. Instead of mandating the change organisation-wide, they worked with teams that were actually willing to try it. Turned those early adopters into success stories, then let the adoption spread organically as other teams saw the benefits.

This pull-based approach probably takes longer, but it's more sustainable than forcing change. The key was having really good internal communication about why the early adopters were succeeding - faster incident resolution, better service quality, more ownership of their destiny rather than waiting for central IT.

They also had to build some surprisingly basic tools, like a service directory that could answer "who do I call when this breaks?" Seems obvious, but apparently it didn't exist before. We should probably be auditing these fundamental capabilities earlier in our client assessments.

What We'd Do Differently

The timeline expectations were probably the biggest challenge. Two years is realistic for this scale of cultural change, but most clients expect visible results in months. We need to be clearer about the difference between quick wins - like better incident response - and fundamental transformation of how reliability works.

The executive commitment here was exceptional. Having the EGM and CTO regularly attend incident reviews sent a powerful signal about priorities. We should be doing more upfront work to secure this level of involvement rather than assuming it will happen naturally.

They could have been more systematic about baseline measurement too. While the business-function SLOs were clever, they missed some opportunities to demonstrate improvement over time. We're probably better positioned to help clients establish proper before/after metrics from day one.

The Real Lesson

The overarching insight is that SRE transformation is fundamentally about organisational change, not technical implementation. The Prometheus setup was the easy part. Changing how people think about ownership, responsibility, and learning from failure - that's where the real work happens.

This aligns with our QCE methodology's emphasis on holistic transformation, but it's a good reminder that we need to be even more explicit about the change management aspects. The technical patterns are well-established now. The people patterns are still the hard part.

I'm curious what you think about applying some of these approaches to our current client contexts. The talent investment strategy in particular seems like something we should be suggesting more often, even though it requires a bigger upfront commitment from leadership. And that accountability mechanism in the incident forums - that could be really powerful if we design it in properly from the start.